Ten and a half hours of sleep would have been nicer if the wind hadn’t started blowing, and if my body hadn’t decided to punish me for the hubris of thinking I could eat again last night. I had to get up twice, and let me tell you that leaving a cozy tent for a gale-filled, sub-freezing night was less than enticing.

I was hopelessly awake before 7, though I had no interest in budging from my sleeping bag. Our alarm-scratch wouldn’t even come until 7:30.

I reached a hand up to rub sleep from my eyes and discovered that my crow’s feet were sunburned. So were my eyebrows (which were also full of sand from yesterday’s scree-ski), and … oh, god… my nose. The skin around my nostrils which – of course! I hadn’t put sunscreen on, because who puts sunscreen there? The sun does not shine there! – were burned so badly I could feel blisters.

My guts roiled and cramped. I groaned and pulled the sleeping bag tighter around my head.

“How you feeling?” Dustin asked. Guess he’d run out of sleeping oomph too.

“Like a crispy fried piece of garbage,” I muttered.

“I know what you mean by crispy fried,” he said. His face and nose had suffered the same fate as mine.

Pro tip, kids: when you’re a lily-white child hiking on a snowfield at 19,000 feet, do not mess around with your sunscreen. Those burning rays are BOUNCING AROUND and they will get you EVERYWHERE. If you’re not wearing a hat, even the scalp under your hair is not safe.

We moved very, very slowly as we got ourselves ready and packed up for the day. I could not bring myself to wash my deep-fried face when Mandela came with warm water. A little eyebrow sand builds character, right?

“How’s everyone feeling today?” Gideon asked at breakfast.

“I can’t believe I climbed that mountain yesterday!” Nyla said. “Like… I really can’t believe it.” (She couldn’t. We heard this phrase a lot over the following days.)

I just grumbled and grimaced at my tea. I certainly didn’t feel good enough to be communicating yet.

“Easy day today,” Gideon reassured us. “Just four hours. All down. Hakuna matata.”

At least I don’t need to use my face much for hiking.

I tried to placate the gods of digestive distress by not eating much. Instead: double water. One thing that can be said for going downhill is that it does not require nearly as many calories as going up.

By the time we left camp shortly after nine, most of the people summitting today were already on their ways back down. I didn’t envy them hiking in this wind. Shortly after leaving camp, we heard a huge collective shout. When we turned back, we saw a tent sailing thirty feet above the camp.

“Hope no one was in there,” Gideon said.

All I could think was how much harder our summit day would have been in the wind. Our weather had been so wonderful.

Today’s four-hour trip would have been tacked on to the end of our summit day if we’d followed the original itinerary. I spent the whole day feeling grateful that we hadn’t.

“Oooh, what are those?” I asked Gideon as we tromped past a pair of rusty-looking carts abandoned several meters off the side of the trail. “Someone had a good idea for moving gear around up here that didn’t end so well?” I imagined some greedy guiding company thinking they could get one guy to carry way more than 80 pounds if he just used this super-awkward wheelbarrow thingy. I could imagine how that had gone on these steep, rocky trails.

“No, they’re stretchers,” Gideon said. “If someone has to be evacuated down without a helicopter. The National Park Service provides them.”

Oh. That’s a much less funny mental image. If someone needs to be rushed down the mountain and can’t go on their own two feet, even with help, a helicopter is always be the fastest, safest option. But sometimes helicopters can’t come, because of weather or – God forbid – too much demand. We’d seen or heard more than a dozen helicopters coming and going during our days on the mountain. Thank goodness we’d all climbed the mountain with respect, pole pole, and could bring ourselves down on our own two feet.

A progression of the mountain, in retreat:

I was surprised how quickly we came out of the Alpine Dessert back into the land of plants.

The descent felt fairly gentle until we got to Millennium Camp, around 12,500 feet, at which point the trail occasionally took staircase-style downward plunges on rocky paths that have been cemented together to prevent the rains from washing them out. Sometimes, deep channels ran along either side where the rains have taken out their fury instead.

“You know,” Nyla said as we took a break at one point and Yona deposited her pack beside her so she could get to water and snacks. “Getting someone else to carry my pack was what made it possible for me to get to the top. I’m so glad I did that.” She turned to Gideon. “You should offer that to people right from the start.”

“We do,” Gideon said.

“What? I didn’t know that! If I’d known that, I’d have signed up right away!”

I snorted. “No you wouldn’t have.”

“Of course I would have!”

“No, you’d have said, ‘I don’t need that kind of help! I’ve been training for months! I’ll carry my own damned bag.'”

“Oh,” she said. “You’re probably right.”

Dustin laughed because he knew I was right.

“But now that I know what it’s like at elevation,” she said, “I would do it every time. Yona saved my life.”

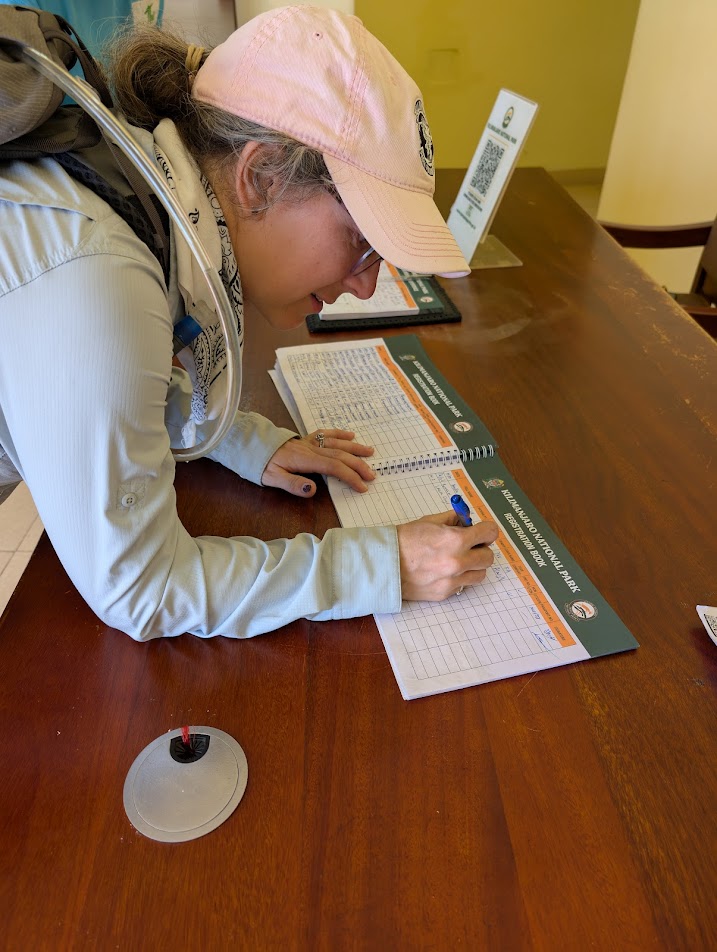

Once we were settled and soaking in mugs of hot chocolate and piles of popcorn, we began the process of sorting out tips for our crew. I considered not posting about this, because I hate discussing all things to do with money, but because it was such a frustrating (and in certain ways interesting) part of the adventure, I can’t refrain from a bit of philosophizing. You can skip from this photo to the next if you’re not interested.

You are not supposed to bring more than $100 onto the mountain with you. In fact, we signed a statement declaring this to be the case as part of the permitting process to get onto the mountain. However, cash tips well in excess of $100 are expected to be handed out the day after summitting which, for all except the most foolhardy, means on the mountain. Everyone signs the paper; everyone knows you are lying.

But since now you can’t complain if someone steals all your money on the mountain, the only option is to keep it on your person at all times. This can be a royal pain when you don’t have huge, zipping pants pockets. I had a travel pouch meant to be worn under my clothes, but after soaking that with sweat on Day 1, I made alternate arrangements which involved moving it here and there throughout the day. I do not recommend this either, but I don’t have a better idea.

We got guidance ahead of time on how much tips would be appropriate for which jobs. “Can’t we just give it all to Gideon and make him divide it up??” we’d begged Cian early on. Cian agreed that the system is arcane and difficult, and agreed to tell Gideon we would do just that. However:

Once you’re up on the mountain, you find that some people really go above and beyond. Our porters worked hard for us, every single one of them, but Omari tending the toilet tent was worth his weight in gold. Mandela who always came to find us at the end of our hike and offered to carry our bags the last quarter mile? Who brought morning tea to our tents and heckled us into taking second servings at dinner? He made the trip brighter and better in meaningful ways. Yona saving Nyla’s life (her words) by carrying her bag for five days? Chaji for carrying my bag to the summit and cheerleading the whole way up? Emanuel and his helpers for feeding us like kings in the most improbable locations? The kid who had to wash all the dishes from our kingly meals?

These men earned the extra recognition, and until our world comes up with a better system, tipping is it. They deserve it from your hands, with a smile on your face and all the love in the world shining through for some of the shitty (literally) jobs they did that made your life on the mountain so unexpectedly comfortable.

But seriously, friends. We’ve gotta come up with a better way. Tipping made up a substantial portion of our trip budget. You look at the prices of guided trips, and unless you’re already thinking about tipping, that price gives you no idea how much the trip is going to cost. If you’re considering planning a trip, this is worth keeping in mind ahead of time.

Okay. /soapbox. Please enjoy this nice picture of some misty hills that Dustin took.

We started our last day’s hike on the early side, to try and get ahead of a little of the traffic that would be checking out at the Mweka Gate throughout the day. There are seven trailheads you can use to start your journey up Kilimanjaro, but only two that bring you back down, and Mweka is the more heavily trafficked. I’ve totally lost a grip on my mountain-traffic math by now, but I can tell you, the number of bodies filtering down today was quite immense.

I spent most of the last day taking pictures of wildlife, as it had once again become abundant. I couldn’t get over how many brand new plants I was seeing, that I’d never seen before in my life, and also how many plants I recognized from visiting greenhouses in South Dakota. Plants they sell as summer annuals grew wild here in the rainforest. Bushes of impantiens. Morning glories and nasturtiums climbing up giant ferns. Those fuzzy little purple guys.

elephant trunk flower

I know this will come as a shock, but I’m an absolutely terrible photographer. Of the dozens of photos I took of wildflowers, mushrooms, and odd mosses, the above are about the sum total of what came out (at least mostly) in focus. Here’s a couple better ones from Dustin:

Not quite halfway through our final day’s descent, we heard a commotion behind us. Gideon hurried up.

“There’s a stretcher coming through. Move to the side, move to the side.”

Lo and behold, here came one of the awkward, one-wheeled carts we’d seen way above. Four porters balanced and guided it on each side. A man was laid out on its length as if in a body bag, and he did not look a lot better than a corpse. Closer inspection revealed that it was actually a sleeping bag, and he’d been cinched into it as tight as a cocoon. I’m not sure how far he’d come on the thing, but I couldn imagine the bumpy ride he’d had.

“He spent the night in Crater Camp,” Gideon said. “It’s not safe. This happens a lot to people who sleep there.” In this case, “there” meant at almost 19,000 feet. “They tried to get him to take a helicopter from Barafu last night, but he wouldn’t.”

Not very long after, we – the slowest hikers on the mountain – passed an enormous group of people. The line of twenty+ clients inched along, interspersed with guides who muttered words of encouragement. None of them really caught my ear until we got up near the front of the line and I heard a guide say to the client right ahead of him, “before we take everyone else back to the hotel, I think we’d better take you to the hospital, okay?”

“Okay,” the woman whimpered in the most pitiful voice I’d ever heard. To her credit, she was still moving on her own two feet.

This mountain is a tough place. Many fall victim to their own hubris, but some simply aren’t suited to reach for high altitudes. “They do not belong to the mountain,” Gideon said later of people who have battled for the top, sometimes over and over again, only to be turned away by the various incarnations of altitude sickness.

After three-ish miles, our trail joined up with a road. As we arrived, the EMT van was just pulling in to collect our friend the Stretcher Man. It looked like he wasn’t the only person waiting for a ride.

The rest of the walk to the bottom passed in dust in mildness. We ended our hike at 5,300 feet, having descended almost exactly 10,000 feet over the last two days. My knees handled it better than expected, but after sitting still at the bottom for an hour while we waited for our certificates, my legs decided enough was enough. I might have wobbled a bit on the trip down to the bus.

We finished our day at a lunch hall with real plumbing, where assistant cook Mmari made us a lovely farewell lunch. (Emanuel had been called off the mountain a day early to join a camping safari trip. Poor dude deserves two weeks off once they set him free.)

Before getting back onto the bus for Arusha, our crew got together and serenaded us with songs and rather more dancing than my knees had expected. By now, their tunes were familiar, and I joyfully joined in on the “hakuna matata” bits and all the clapping bits. They’d sung for us on the bus ride to the mountain as well, but now we knew their names and faces and now everyone (knees excepted) was in a party mood.

They kept singing through most of the three-hour bus-ride home. At some point, someone acquired beers, which led to the most painful rendition of “My Heart Will Go On” that I’ve ever heard. Most of their songs devolved into odes to Mama Simba, whom by now the entire crew was entirely devoted to. Poor Mama Simba just wanted to take a nap.

We checked back into our hotel in Arusha covered in dust and looking decidedly frayed around the edges. Our left-behind bags were withdrawn from storage and we all plunged directly into showers followed by the first truly clean clothing in eight days. Eyebrows were de-sanded and blistered noses lotioned.

The sense of accomplishment is real, and so is the sense of relief in knowing that when you need to pee at 2am, you don’t have to go outside.

- Starting Elevation: 15,169 feet (4,623m)

- Ending Elevation: 5,393 feet (1,640m)

- Cumulative Loss: 9,776 feet

- Approximate Miles: 11

- Average Pace: 41’40”/mile

- Swahili phrases learned: “samahani” (excuse me)