I’ve chosen the title because we have spent a LOT of time in Mexico over the last fourteen years, and I think maybe I’ll try to go back and post some of our past adventures? But for now, I shall start present and work back.

Today I learned how to make chocolate!

While perusing possible adventures for our stay this year, Dustin came across the Choco Museo, which offers a variety of workshops purporting to teach guests how to make chocolate truffles, filled chocolates, chocolate beverages, and even mole sauce.

I say “purportedly” because I have this memory from high school where, to fulfill the requirement of learning the scientific process and conducting your own experiment, some students chose to “make chocolate” according to several different recipes, and then test them (feed them to their classmates) to determine which recipe was best. I remember taste-testing dozens of tiny bites of “chocolate” on behalf of three or four students doing the same experiment, and – already a chocolate snob at the age of 16 – I remember thinking every last sample was terrible.

That, I assumed, is simply what happens when untrained gringos with no specialized equipment try to make chocolate.

But I love chocolate and I love trying new things, so I was all in anyway.

We chose the Total Chocolate Experience workshop, which promised that we would roast and grind our own cacao beans, make three chocolate drinks, learn to make chocolate ganache and to temper chocolate, make chocolate truffles, and make filled chocolates, all of which we could take home to amaze our friends and family (or just devour quietly in a dark room).

We made fun of the hats when we saw them in the website’s photos, but when they handed them to us at the workshop table, they were basically irresistible.

Here, for your enjoyment, is a Very Brief History of Chocolate (as presented during our workshop, though errors are probably due to retention rather than instruction problems):

The Olmecs began the human relationship with cacao trees as long as 2,000 years ago, but it was the Maya who really went wild with it, perfecting fermentation, drying, and roasting techniques, as well as actively cultivating cacao trees in the southern parts of Mexico. The Maya started trading cacao beans to the Aztecs, who – unable to grow their own trees in their more northern climate – considered the beans a much more precious resource. They used cacao beans as currency and the drinks they brewed were for special occasions only. The only sweetener available at the time was honey, but even this was used very sparingly. Instead, the very bitter drink was flavored with chili, vanilla, corn, annatto, and other endemic spices.

The Aztecs considered cacao to be the food of the gods, so when the Spanish conquistadors showed up out of the blue, the conversation went something like this (as relayed by Danny, our guide on a tour to San Sebastian):

Aztecs: Hello mysterious white strangers who come bearing baffling technology and wearing fancy pants! You must be sent from the gods! We’re happy to report we’ve been working hard to perfect the cacao you blessed us with! Please, let your holy selves enjoy a steamy mug of your holy brew!

Conquistadors: Why yes, yes, that’s us, definitely gods. Thanks for the delicious – BLAH COUGH BLEH YUCK YUCK BLECH EW WHY HOW WHAT IS THIS VILE STUFF?!

And then some violence ensued.

Turns out the Spanish were not big into bitterness, but they were big fans of the energy the cacao drink gave them, so they brought it back to Spain. The Catholic church condemned it as a heathen drink, and then set about converting the beans to Christianity. They mixed the cacao with heaps of sugar, milk, cinnamon, clove, and anise, turning it into the cocoa we are most familiar with today.

The gal leading our workshop, Lizzette, recounted this history while she walked us through the initial steps of preparing cacao beans. Starting with a pile of beans that had already been fermented and sun-dried, we roasted the beans until they popped and crackled, the whole room taking on an amazing, roasty chocolatey smell. We then peeled the beans, separating the papery husks from the whole and broken beans (called nibs).

Once enough snap-popping had occurred, Lizzette poured the roasted beans out on the granite counter and we began picking off their papery husks.

“You can eat them just like this,” Lizzette said. “Go ahead and try one.”

And I did, even though I knew exactly how it would end.

Lizzette added the discarded cacao bean husks to a pot of boiling water to make the first of our three chocolate beverages: chocolate tea. We sipped this surprisingly chocolately drink from very tiny mugs. I would have that for breakfast. I didn’t even miss the dairy very much.

Now what do we do? We grind them up!

“Keep going until it looks like peanut butter,” Lizzette instructed. It turns out the Mexican-Spanish word for peanut butter – “cacahuate” – has a lot in common with the original Nahuatl (Aztec) word for chocolate – “cacahuatl.” (I went online to verify I had the spellings right and found out there’s loads of controversy about the original Nahuatl word. Maybe “cacahuatl,” but also maybe “chocolatl”? Or maybe “xocalia”? Anyway. The Spanish got their hands on it and it became the “chocolate” we know and love.)

We scraped the results of our grinding efforts into the shell of a jicara fruit (not, like I’d initially thought, the shell of a seriously monster coconut). Lizzette added guajillo chili powder, honey, and a portion of the cacao tea. The amount of honey seemed a little unreasonable – I don’t like things overly sweet – but I had already forgotten how desperately bitter pure cacao is. The bitter beans ate that 1/3 cup of honey for breakfast and left us with a very balanced flavor.

One mixes this sweetened variation on the ancient version of cacahuatl by pouring it from one jicara shell to another until it is all dissolved, just a few chewy bits left over from the chilis and our meager hand-grinding skills.

We scooped the resulting hot beverage (the Maya and Spanish would have liked that, the Aztecs preferred theirs cold) into tiny jicara shells and drank it up.

Lizzette was moving into the part of the history lesson where she talked about the fancy, entitled Spaniards showing up with their own ideas of how things should go, when I interrupted.

“Speaking of entitled white people, can I, uh, have some more of that?” I’d emptied my tiny jicara shell, and was eyeballing the remaining goodness in the big shell.

Lizzette blinked at me. “No one has ever asked for more before,” she said. “But of course, it’s all for you.”

No one?? This stuff was delicious. Between us, Dustin and I drained the entire big jicara shell.

Back to the entitled Spaniards. As mentioned, all the rituals and spices surrounding the traditional Aztec version of cacahuatl disagreed with their Catholic sensibilities, so they took cacao home to Europe and turned it into something that better suited their scripture (palate). Instead of chilis or annatto or any other new-world flavors, they busted out cinnamon, cloves, anise, and sugar. So much sugar.

I was very pleased to discover we’d be grinding the rest of our cacao beans like good little industrialists. Bring on the crank grinder!

First, the beans went through the grinder on their own, creating a paste that was coarse (though less coarse than the stuff we’d ground by hand). This product is apparently called “chocolate liquor” in the English-speaking chocolate world, and – more sensibly – “pure paste” in Spanish.

“Taste it now,” Lizzette said after the first grinding. I squinted at her suspiciously. I’d fallen for this once. Why would the ground beans taste any less bitter than the whole beans? But I did it anyway, because I’m all about the experience.

“They’re not as bitter,” Dustin declared. Maybe he was right, or maybe I’m right and it’s just easier to chew up and quickly swallow ground cacao.

Next, the beans went through the grinder a second time in the company of three very large spoonsful of sugar. I didn’t even mentally object to all the sugar, this time. The resulting paste was very smooth indeed.

Lizzette added a quantity of this paste along with the Spanish spices to a pot of hot milk. Now we would drink like Spanish kings and popes!

We received bigger cups of this beverage (see first photo), possibly because this is the version of hot chocolate that most of the gringos prefer? And it was tasty – I’m always there for a little dairy and cinnamon with my hot chocolate – but I would take the cacao-chili-honey cacahautl drink over this one any day of the week.

We shaped the remaining ground cocoa into a star, a moon, a bunny, and a chick that we could take home and use to make our own Spanish hot cocoa.

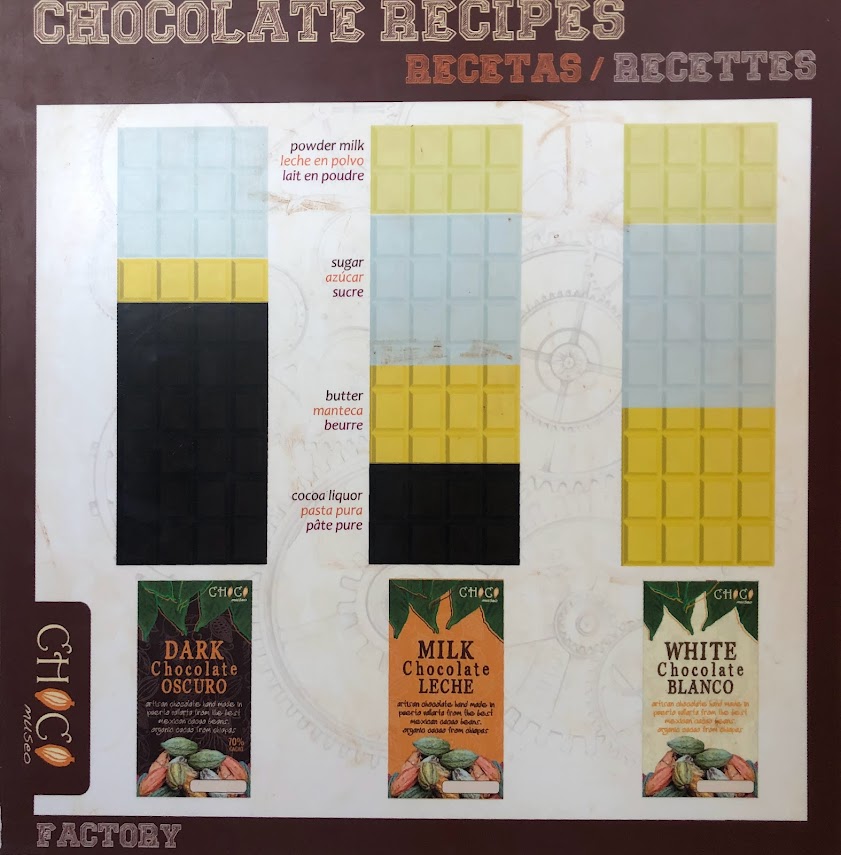

If we’d REALLY been making our own chocolate, start to finish, we would now press our ground cacao in order to extract the cocoa butter, leaving behind cocoa powder. Chocolate bars, as you and I know them, are made by combining the pure paste (what we’d just made) with extra cocoa butter, sugar, and sometimes milk.

Instead of doing that, because that part takes way more time than our 3-hour workshop could accommodate, Lizzette busted out the chocolate that was ready to go.

“Now we make the ganache,” Lizzette said. We learned the difference between soft, medium, and firm ganache (1:2 parts chocolate to cream, 1:1 parts chocolate to cream, and 2:1 parts chocolate to cream) and then we got to choose flavors.

We debated, but only briefly, and settled on chili, cinnamon, and rum (since I quite dislike tequila). We mixed it up, then sent it off to chill while we moved on to the next and greatest of our chocolate lessons.

“Time to temper the chocolate,” Lizzette announced, bringing out a massive bowl of melted chocolate. My fingers and toes wiggled. Cocoa drinks and ganache fillings are fine, but this was why I really came today.

Tempering chocolate is an arcane and devilish skill. I spent about three weeks of the 2021 holiday season trying to teach myself to temper chocolate. The results included a pile of very lumpy peanut butter balls, some much more respectable-looking dipped candied orange slices… and also chocolate on every surface in my kitchen, my instant-read thermometer entirely submerged in melted chocolate, a favorite chopstick broken in half when I tried to pull it out of the rock-hard bowl of cooled chocolate, and not just a little swearing.

The last thing I swore was that I’d never try it again.

But I didn’t really mean it. I reeeeally wanted to know how to temper chocolate, and I firmly believed there was a better way to do it than to chocolate-dip my entire thermometer, I just needed a pro to show me what it was.

“The chocolate has to be 45 degrees [115 F],” Lizzette said, zapping the enormous bowl with a ray gun. “It’s 41 now. Needs a little more time.” She stuck it back in the microwave.

I grabbed Dustin’s shoulder. “That’s the thing my dad had in the park!” I hissed. We’d spent one glorious afternoon in Yellowstone wandering around with an infrared remote thermometer, zapping hot springs and trees and patches of ground and marveling at the temperatures produced by the thermal basin. Now here’s Lizzette, using it on chocolate.

If you ever need a gift idea for me……

Once the chocolate reached a satisfactory 46 degrees – “one degree too much is okay” – Lizzette poured it right out on the granite countertop.

“The stone is cold and will help reduce to the right temperature, 27 degrees [81 F],” she explained. “We help it like this.” She took a large putty knife and began spreading the chocolate over the granite, then used the knife to scrape it back in toward the center, cleaning the putty knife on a wide, flat spatula.

“Your turn!” she held the putty knife and spatula out to me.

While we spread and scraped, Lizzette monitored the cooling of the chocolate with her chocolate ray gun. “That’s good,” she announced after a few minutes. We returned the tools to her, and she scraped the chocolate right off the edge of the counter, back into the bowl.

Back into the microwave the chocolate went, just for a bit, until it hit the magical temperature of 31 degrees [88 F].

“Who figured this out?” I asked. “I mean… asking who ate the first oyster is easy compared to this. All that guy had to be was drunk or desperate. But who figured out three precise temperatures in the right order would make chocolate hard and shiny?”

Even Lizzette, basically a chocolate master, did not know the answer to this.

[Even the internet is mostly mum on this point, though crumbs point toward Swiss chocolatier Lindt’s invention of the conching (smoothing) process in 1879 as the likely first step. I guess if someone was going to figure this out, the folks who perfected watchmaking would be good candidates.]

Now we chose molds for our shaped chocolates and coated them with our tempered chocolate. Once hardened, these shells would be filled with the flavored ganache we’d made earlier.

A second batch of unflavored firm ganache was provided, and we rolled it into balls to be dipped and topped for truffles.

Did you know that after you dip your ganache ball into the tempered chocolate, you’re not supposed to tap it on the edge of the bowl to get the extra chocolate out?? This can cause your ganache ball to get stuck on the tines of the fork. (Suddenly, all my lumpy peanut butter balls made so much more sense.) Instead, you must bob the fork up and down over the center of the chocolate in the bowl, barely allowing the underside to touch the surface each time.

Haha, no we’re not.

These are easily the most beautiful chocolate-coated things I’ve ever made, though the single chocolate Lizzette dipped as an example was still miles beyond our slightly dribbly efforts.

Perfection or no, we boxed up all our truffles, mice, and lumpy bunnies. I was sorry I couldn’t cart off all the leftover chocolate drinks, too, but the giftshop downstairs was more than happy to sell me cacao beans in every state, cacao husks ready to make tea, and any number of other delicious possibilities. We selected more than a few extra treats before heading home to show off our chocolates to Grandma, just like proud kindergarteners toddling home with our first drawings.

I’ll be back to let you know how it goes when I try tempering chocolate on my own again next Christmas…